Egyptian Geography/Nile River

Egyptian civilization developed along the banks of the Nile River, which flows from south to north into the Mediterranean Sea. Because of the direction of the current, the southern part of the country is referred to as "Upper" Egypt (i.e., upstream), and the northern part (including the Delta, where the river splits into multiple branches) is called "Lower" Egypt. Until the construction of the Aswan High Dam in the 1960s, the Nile flooded every year during the summer months. When the floodwaters withdrew they left behind a layer of rich black silt, which the Egyptians used to fertilize their crops. Thus black was the color of life for the Egyptians, and they called their country "Kemet," meaning "the black land." This stood in contrast to the "Deshret" ("red land"), the land of the dead, referring to the inhospitable sands of the deserts which surround the Nile valley. Because it was the annual flood that created the fertile conditions allowing for life in the middle of a harsh desert environment, the ancient Greek historian Herodotus called Egypt the "gift of the Nile."

Suggested reading:

Manuelian, Peter Der. "The Nile," and Picardo, Nicholas. "The Desert & the Oases." In Manuelian, Peter Der. 30-Second Ancient Egypt: The 50 Most Important Achievements of a Timeless Civilization Each Explained in Half a Minute. London: Ivy Press, 2014, pp. 16-19.

What and when was the Old Kingdom?

Broadly speaking, historians divide Egyptian history into three "Kingdoms" (Old, Middle, and New), each of which is divided into multiple dynasties (successive generations of a ruling family). The Old Kingdom (Dynasties 3-8, about 2650-2130 BCE) was the first manifestation of a unified Egyptian state, which joined the northern (Nile delta) and southern (Nile valley) halves of the country under a single ruler. This was a period of strong central government, which allowed Egypt’s kings to organize the tremendous labor force necessary for massive building projects like the pyramids (built in Dynasty 4).

Suggested reading:

Freed, Rita E. "Egypt in the Age of the Pyramids." In Markowitz, Yvonne J., Joyce L. Haynes and Rita E. Freed. Egypt in the Age of the Pyramids: Highlights from the Harvard University-Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Expedition. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2002, pp. 17-20.

What is a pharaoh? How was Egyptian society structured?

Egyptian society was strictly hierarchical, with the pharaoh (king) and royal family at the top. The word "pharaoh" comes from the ancient Egyptian "per-aa", meaning "Great House" or "Palace" (as modern Americans can refer to "the White House" and mean the President). The king (or, occasionally, queen) was believed to be the living embodiment of the god Horus, a sun god. According to myth, Horus fought against Seth, the god of chaos, to bring order and justice to the world. The king was meant to uphold this divine order (called "maat") in human society. Below the king in the social structure were priests, the elite officials who oversaw the administration of the country, and skilled artists and craftspeople. At the bottom were the common people, who worked mainly as farmers or were employed on great building projects like the pyramids.

Suggested reading:

Freed, Rita E. "Life During the Pyramid Age." In Markowitz, Yvonne J., Joyce L. Haynes and Rita E. Freed. Egypt in the Age of the Pyramids: Highlights from the Harvard University-Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Expedition. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2002, pp. 26-31.

Manuelian, Peter Der. "Pharaoh." In Manuelian, Peter Der. 30-Second Ancient Egypt: The 50 Most Important Achievements of a Timeless Civilization Each Explained in Half a Minute. London: Ivy Press, 2014, pp. 22-23.

Royal attire and symbols

Egyptian kings wore several different styles of crown. Most common were the "Red Crown" (representing Lower Egypt) and the "White Crown" (representing Upper Egypt); the two were frequently worn together as the "Double Crown" to demonstrate the king’s rule over the entire unified country. Kings were also shown wearing the "nemes," a striped headdress (famously seen on the gold mask of Tutankhamun from the Valley of the Kings; at Giza, it can be seen on the head of the Great Sphinx, as well as on a number of royal statues). In addition to the crown or headdress the king wore a uraeus, a representation of a fierce protective cobra which was worn on the forehead to frighten pharaoh’s enemies. Kings also often wore a ceremonial braided false beard and carried one or more official scepters, maces, or staffs.

What is a pyramid?

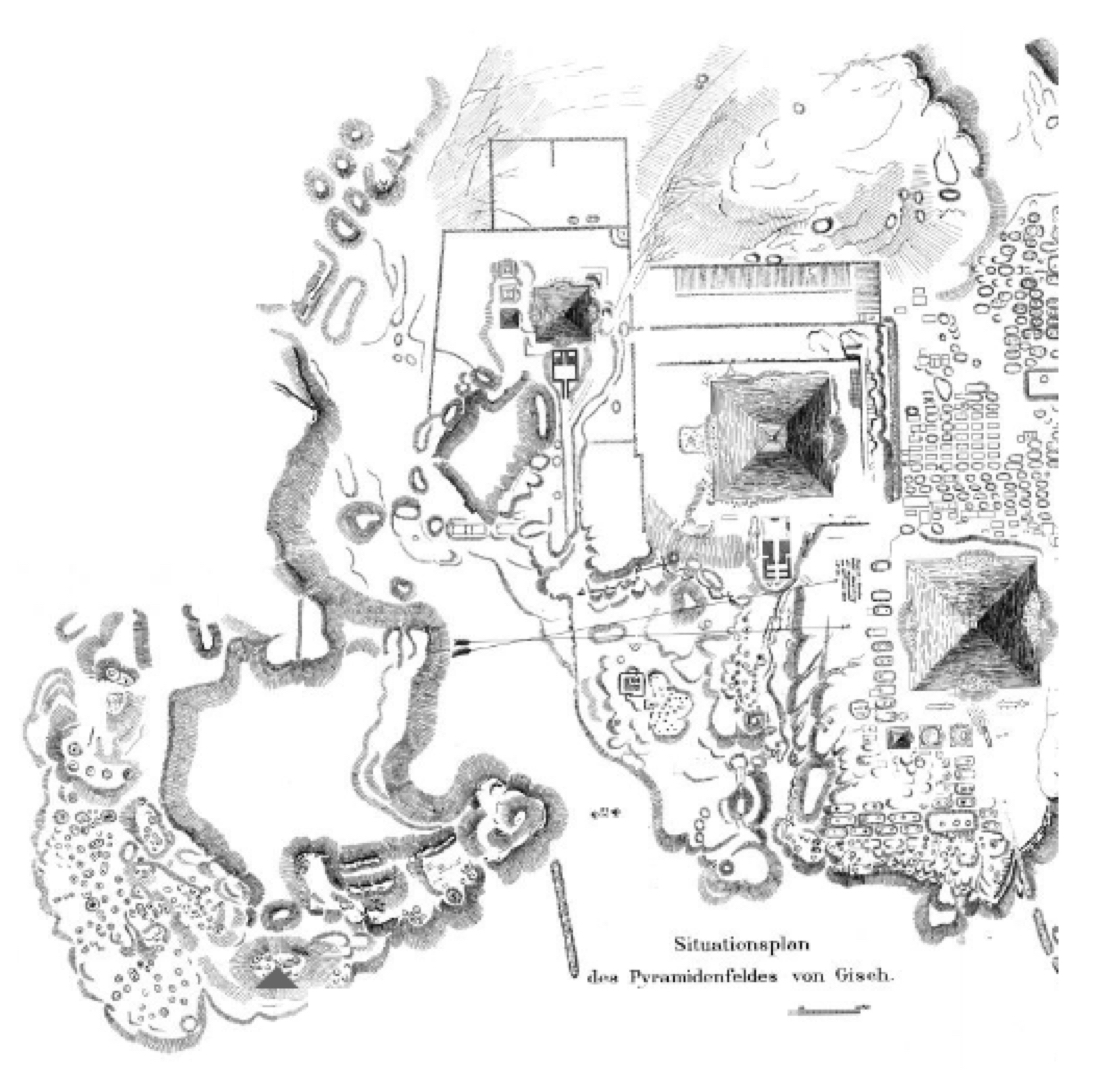

Pyramids were the burial places for Egyptian royalty during the Old Kingdom (and in some later periods as well). The three large pyramids at Giza were built for three generations of Egyptian kings: Khufu, his son Khafre, and his grandson Menkaure. There are also several smaller pyramids at Giza, constructed for these kings’ wives and mothers. In Egyptian mythology, the world was created by raising a mound of land out of the sea; the triangular shape of the pyramid was meant to represent that first hill, so that the king could use the power of creation to be "reborn" into the afterlife. Although pyramids were built at multiple sites in Egypt, the ones at Giza are the largest, with the Great Pyramid of Khufu standing about 481 feet tall.

Suggested reading:

Lehner, Mark. "The Pyramid as Icon." In The Complete Pyramids: Solving the Ancient Mysteries. London: Thames and Hudson, 1997, pp. 34-35.

Allen, James P. "Why a Pyramid? Pyramid Religion." In Hawass, Zahi, ed. The Treasures of the Pyramids. Vercelli, Italy: White Star Publishers, 2003, pp. 22-27.

Pyramid Complexes

In addition to the pyramid itself, each royal burial complex had two temples associated with it: one at the river’s edge (the "valley temple"), with a harbor where the boats carrying the king’s body and funeral equipment would have docked; and one located next to the pyramid itself (the "pyramid temple" or "mortuary temple"). The two temples were connected by a long covered causeway, which the funerary procession would have followed on its way to bury the king in his pyramid. Each temple had a rotating staff of priests, who continued to serve the semi-divine king’s cult long after his death.

Suggested reading:

Lehner, Mark. "The Standard Pyramid Complex." In The Complete Pyramids: Solving the Ancient Mysteries. London: Thames and Hudson, 1997, pp. 18-19.

Boats

Because of Egypt’s location along the Nile, boats were a primary means of transportation, and the imagery of boats extends into mythology. The sun was believed to cross the sky in a boat, steered by the sun god Re. In death, the king hoped to become like Re and join him in his journey across the heavens. Several boats were buried in special pits beside the pyramids at Giza; these were perhaps meant to serve the king in the afterlife, and/or may have been used as part of the funeral procession to transport the king’s body to Giza for burial.

Suggested reading:

Altenmüller, Hartwig. "Funerary Boats and Boat Pits of the Old Kingdom." In Filip Coppens, ed. Abusir and Saqqara in the year 2001. Proceedings of the Symposium (Prague, September 25th-27th, 2001). Archiv Orientální 70, No. 3 (August 2002). Prague: Oriental Institute, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, pp. 269-290.

Jones, Dilwyn. Boats. Egyptian Bookshelf. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1995.

Who built the pyramids?

Contrary to popular belief, the pyramids were not built by slaves (or aliens!). According to recent work at Giza, which has revealed the town and tombs of the pyramid builders, the workforce likely consisted of 20,000 to 30,000 native Egyptians. Some of them would have been skilled craftsmen, but most were manual laborers employed in cutting and hauling the massive blocks of stone. Egypt did not use money during this time period, so the workers were paid in food, primarily bread and beer.

Suggested reading:

Morell, Virginia. "The Pyramid Builders." National Geographic Magazine (November 2001): http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/data/2001/11/01/html/ft_20011101.5.fulltext.html

Lehner, Mark. "The Living Pyramid." In The Complete Pyramids: Solving the Ancient Mysteries. London: Thames and Hudson, 1997, pp. 200-225.

Website of the Ancient Egypt Research Association (AERA), currently exploring Giza’s "Lost City" of the pyramid builders: http://www.aeraweb.org/

What is the Sphinx?

In ancient Egypt, a sphinx was a mythical creature with the body of a lion (symbolizing the strength and power of the kingship) and a human head (usually that of the ruling king, wearing the royal headdress). The colossal Great Sphinx of Giza and its associated temple are located near the valley temple of Khafre, builder of the second pyramid at Giza, and are generally believed to have been built during his reign. The Sphinx is one of the earliest and largest monolithic statues in the world, 241 feet (73.5 m) long, 63 feet (19 m) wide, and 66 feet (20 m) high. During the New Kingdom (roughly a thousand years after its construction), the Sphinx was worshipped as Horemakhet ("Horus in the horizon"), a form of the sun god.

Suggested reading:

Lehner, Mark. "The Great Sphinx." In The Complete Pyramids: Solving the Ancient Mysteries. London: Thames and Hudson, 1997, pp. 127-133.

Lehner, Mark. "Reconstructing the Sphinx." Cambridge Archaeological Journal 2 no. 1 (April 1992), pp. 3-26.

What is a mastaba tomb?

The term "mastaba" (Arabic for "bench") refers to the many bench-shaped tombs that surround the pyramids. These tombs generally consist of a rectangular building made of limestone blocks or mud bricks, containing a small room or group of rooms (chapel) where offerings were made to the deceased. These chapels were often decorated with scenes of daily life, as well as images of food (bread, beer, and meat) to magically "feed" the deceased in the afterlife. Below the chapel, one or more shafts descend into the bedrock of the plateau, containing the burials of the tomb owner and sometimes his (or her) family.

Suggested reading:

Jánosi, Peter. "The Tombs of Officials. Houses of Eternity." In Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999, pp. 26–39.

Who was buried at Giza?

First and foremost, Giza was a royal cemetery. Kings themselves were buried there, inside the three great pyramids. But there are also thousands of other ancient burials at Giza. Many of these were for other members of the royal family. Queens sometimes had smaller, subsidiary pyramids next to their husbands’, and the cemetery to the east of the Great Pyramid contains tombs of princes, princesses, and other relatives of the king. Most of the remaining tombs across the plateau belonged to society’s elite: scribes, priests, bureaucrats, overseers of the workers who built the pyramids, and other high officials who served the royal court.

Suggested reading:

Markowitz, Yvonne J. "Excavating Giza." In Markowitz, Yvonne J., Joyce L. Haynes and Rita E. Freed. Egypt in the Age of the Pyramids: Highlights from the Harvard University-Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Expedition. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2002, pp. 33-45.

Manuelian, Peter Der. "The Tombs of the High Officials at Giza." In Hawass, Zahi, ed. The Treasures of the Pyramids. Vercelli, Italy: White Star Publishers, 2003, pp. 190-220.

Egyptian funerary beliefs

The ancient Egyptians believed in an afterlife which was fundamentally similar to life as they knew it, filled with the same activities and necessities (food, shelter, clothing) that they experienced on a daily basis. Thus tombs were thought of as "houses for eternity," which the spirit of the deceased would inhabit forever. They were filled with the sorts of things people expected to need – both full-size versions and durable, small-scale models of them – commonly including plates for food and beer jars. The walls of the tomb chapel were frequently carved with requests for food and drink, linen cloth, and "all good things" to sustain the spirit in the next world. In addition, the tomb owner’s children or grandchildren would periodically visit the tomb and leave food there for their relatives.

Suggested reading:

Allen, James P. "Some Aspects of the Non-royal Afterlife in the Old Kingdom." In Miroslav Bárta, ed. The Old Kingdom Art and Archaeology. Proceedings of the Conference held in Prague, May 31-June 4, 2004. Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology, 2006, pp. 9-17.

Lehner, Mark. "Tomb and Temple." In The Complete Pyramids: Solving the Ancient Mysteries. London: Thames and Hudson, 1997, pp. 22-30.

Aronin, Rachel. "Burial Equipment." In Manuelian, Peter Der. 30-Second Ancient Egypt: The 50 Most Important Achievements of a Timeless Civilization Each Explained in Half a Minute. London: Ivy Press, 2014, pp. 106-107.

Mummies

The practice of mummifying the dead probably began accidentally, due to the natural drying effects of burial in the desert climate. The Egyptians then developed techniques to preserve the body even further, removing the internal organs and drying the body in salt before wrapping it in linen cloth. Egyptians believed that a person’s spirit remained connected to the body after death, and that if the body were destroyed they would not be able to enter the afterlife. Therefore preserving the body was extremely important, and a number of amulets were included in the mummy’s wrappings to help magically protect it from harm.

Suggested reading:

D’Auria, Sue. "Mummification in Ancient Egypt." In D’Auria, Sue, Peter Lacovara, and Catharine H. Roehrig, eds. Mummies & Magic: The Funerary Arts of Ancient Egypt. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1988, pp. 14-19.

Ikram, Salima. The Mummy in Ancient Egypt: Equipping the Dead for Eternity. London: Thames & Hudson, 1998.

Women at Giza

Relatively few women owned their own tombs at Giza, partially because space on the plateau was reserved for members of the bureaucratic elite who worked for the government, and such administrative positions were mostly held by men. Additionally, providing final resting places for women seems to have been seen as the responsibility of their male relatives, usually husbands, fathers, or sons. Many women appear in the wall decorations of their husbands’ tombs, suggesting that they may have been buried there as well. Women who did have their own tombs were mostly queens and princesses, who, as members of the royal family, had the right to be buried on the plateau.

Suggested reading:

Callender, Vivienne G. "A Contribution to the Burial of Women in the Old Kingdom." In Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2001, Proceedings of the Symposium, Prague, September 25th–27th, 2001. Edited by Filip Coppens. Archiv Orientální 70, no. 3 (August, 2002), pp. 337–350.

Hassan, Ali. The Queens of the Fourth Dynasty. Egypt: S.C.A. Press, 1997.

Roth, Ann Macy. "Little women: gender and hierarchic proportion in Old Kingdom mastaba chapels." In The Old Kingdom Art and Archaeology. Proceedings of the Conference held in Prague, May 31–June 4, 2004. Edited by Miroslav Bárta. Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology, 2006, pp. 281–296.

Writing/Hieroglyphs

The Egyptians had two main systems for writing their language. The first was hieroglyphs, which were not merely "picture-writing" but rather a complex system in which each character stood for a sound or group of sounds, much like letters in many modern languages. One special type of character (called a "determinative") had no sound but instead helped to classify a given word within larger categories. Hieroglyphs were generally carved in stone, and used for important documents such as royal decrees, or religious texts on tomb or temple walls. The second writing system was hieratic, which was a cursive script written in ink on papyrus or fragments of pottery (called ostraca), which was used for everyday things such as letters and legal documents like wills and marriage contracts. Like modern Arabic and Hebrew (to which Egyptian is distantly related), the ancient Egyptian language did not write vowels.

Suggested reading:

Leprohon, Ronald J. "Writing." In Manuelian, Peter Der. 30-Second Ancient Egypt: The 50 Most Important Achievements of a Timeless Civilization Each Explained in Half a Minute. London: Ivy Press, 2014, pp. 120-121.

Fischer, Henry G. Ancient Egyptian Calligraphy. A Beginner's Guide to Writing Hieroglyphs. 4th edition. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999.

Wilkinson, Richard H. Reading Egyptian Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Egyptian Painting and Sculpture. London: Thames & Hudson, 1992.

Gods and Goddesses

Osiris: Osiris was a god of fertility and vegetation. According to myth, he was also the first king of Egypt, and was murdered and dismembered by his jealous brother Seth, the god of chaos. His wife Isis gathered the parts of his body together again and bound them with bandages, creating the first mummy; Osiris was thereafter a god of the dead and ruler of the underworld.

Isis: Isis was the wife of Osiris. Along with her sister Nephthys, she was a protector goddess, particularly of the dead; the two were often shown together on coffins to guard the body. She was believed to have great magical powers and was able to bring her murdered husband Osiris back to life.

Horus: Typically shown in the form of a falcon, or as a man with a falcon’s head, Horus was the son of Osiris and Isis. He fought with his homicidal uncle Seth and claimed the throne of Egypt as the rightful heir of his father Osiris. He was thus the god of kingship, representing order and justice in the world, and was strongly associated with the sun. From the New Kingdom (1550-1070 BCE) on, the Great Sphinx at Giza was thought to represent a solar form of Horus called Horemakhet ("Horus in the horizon").

Anubis: Anubis was the jackal-headed god of the dead, who was associated with mummification and embalming after helping Isis bring Osiris back to life. In the realm of the dead, Anubis also oversaw the "Weighing of the Heart," a method of passing judgment over the deceased to decide who was worthy to enter the afterlife.

Re (or Ra): Re was the primary sun god, represented in many forms but most commonly as a man with a hawk’s head and a headdress consisting of the sun’s disk encircled by a cobra. He was one of the major gods of Egypt throughout much of its history, and was associated with creation, kingship, and renewal.

Hathor: Hathor was the patron goddess of love, music, sexuality/fertility, and rebirth in the next life. She was the daughter of Re, a solar god, and was usually shown as a cow or a woman wearing cow’s horns around a sun disk. Many festivals (involving dancing, drinking, and sometimes ritual sex) were celebrated in her honor. She was mostly associated with Upper Egypt, although she was also important in the area around Memphis (which includes the important royal cemetery sites of Giza and Saqqara).

Bastet: Bastet was a warrior and protective goddess, depicted as a cat (or sometimes lion) or a woman with a cat’s head. She was associated with Lower Egypt (the Nile Delta). Hathor and Bastet are often shown together, representing the two halves of Egypt (for example, the southern door of the Khafre Valley Temple is inscribed for Hathor, and the northern door for Bastet).

Ptah: Ptah was the patron deity of artists and craftsmen, and was particularly prominent in the area around Memphis (which includes the important royal cemetery sites of Giza and Saqqara). He was also an important creator god, who magically made the world by thinking and speaking it into existence.

Amun: Amun was a powerful primordial creator god, whose name means "the hidden one." He is usually shown as a man wearing a headdress with two large feathers on it. He was worshipped as far back as the Old Kingdom but rose to become the king of all the gods during the New Kingdom, when he was associated with the sun god and worshipped as Amun-Re.

Khnum: Khnum was a ram-headed god, who was thought to embody the source of the life-giving Nile River. Because of this, he was also seen as a creator god and was said to have fashioned humanity from clay on a potter’s wheel.

Suggested reading:

Wilkinson, Richard. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2003.Leprohon, Ronald J. "Re, the Sun God," Picardo, Nicholas. "Osiris & Resurrection," and Eaton-Krauss, M. "Amun." In Manuelian, Peter Der. 30-Second Ancient Egypt: The 50 Most Important Achievements of a Timeless Civilization Each Explained in Half a Minute. London: Ivy Press, 2014, pp. 98-101, 104-105.

Elements of Tombs and Tomb Equipment

Suggested reading:

Dodson, Aidan and Salima Ikram. The Tomb in Ancient Egypt. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2008.

False doors: The ancient Egyptians believed that the spirit of an individual continued to inhabit his or her tomb after death. Therefore tombs generally included a magical representation of a door (called "false" by Egyptologists, because it was not actually a functional door) by which the spirit could enter and leave the burial chamber throughout the day. They were typically located in the western wall of the mastaba chapel (west being the direction in which the land of the dead was located), and consisted of carved door jambs and lintels inscribed with the name and image of the deceased and/or members of their family, and a tablet above the door which often showed the tomb owner seated in front of a table laden with offerings (usually food). Surviving family members would also have left offerings of real food in front of the false door, so their relative could continue to eat in the afterlife.

Suggested reading:

Reisner, George A. A History of the Giza Necropolis. Vol. 1. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1942, pp. 372-379.

Offering tables and basins: Egyptians often placed carved stone basins (usually rectangular) or tables (often in the shape of the hieroglyph "hetep," meaning "offering") in front of the false door or elsewhere in the tomb, to receive the food and other offerings left by relatives and priests. These were frequently inscribed with the name and titles of the deceased individual to whom they belonged.

Serdabs: A serdab is a hidden chamber found in some mastaba tombs, typically located in the chapel somewhere near the false door, in which statues of the tomb owner and/or their family members could be placed. These spaces were inaccessible once the tomb was completely built, with only a small window slit opening onto the main room of the chapel. The statues placed in these chambers probably served as stand-ins for the body of the deceased (which was buried farther away, in a shaft underneath the tomb) to receive the offerings made on behalf of the tomb owner.

Statues: Egyptians frequently placed statues in their tombs, believing that the statue could serve as a sort of backup body for the person’s spirit if something were to happen to the actual remains. These statues could show the tomb owner alone, or in a group with their spouse and/or children. They are generally not faithful portraits of what the person actually looked like, but are instead rather generalized versions of what an ideal body would look like: young and healthy, without much attention paid to particular facial features. It is rare indeed for a sculpture to be recognizable as a specific individual; the so-called "reserve heads" (see below) are perhaps the closest that the ancient Egyptians came to what we would now consider "portraiture."

Suggested reading:

Freed, Rita E. "Rethinking the rules for Old Kingdom sculpture. Observations on poses and attributes of limestone statuary from Giza." In The Old Kingdom Art and Archaeology. Proceedings of the Conference held in Prague, May 31–June 4, 2004. Edited by Miroslav Bárta. Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology, 2006, pp. 145 –156.

Grzymski, Krzysztof. "Royal Statuary." In Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999, pp. 50–55.

Servant statues: One particular type of statue found in serdabs is the "servant statue" (more recently known as "serving statues"), so called because they show an individual performing menial labor (usually related to food preparation, such as grinding grain, baking bread, or making beer). They are often somewhat roughly carved, and are only rarely inscribed with the name of the person depicted. These figurines have traditionally been interpreted by Egyptologists as a way for the tomb owner to make sure they would have people to make food for them in the afterlife.

Suggested reading:

Roth, Ann Macy. "The Meaning of Menial Labor: "Servant Statues" in Old Kingdom Serdabs." Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 39 (2002), pp. 103–121.

Breasted, James H. Egyptian Servant Statues. New York: Pantheon Books, 1948.

Reserve heads: A "reserve head" is an unusual kind of statue that is known from just over 30 examples, mostly from Dynasty 4 tombs at Giza. Unlike other ancient Egyptian statues, they are just heads, from the top of the skull to the bottom of the neck, and their faces are far less generic than those found on most sculpture – possibly even portraits. Egyptologists disagree on whether the Egyptians thought reserve heads could become spare heads for the dead in their afterlife (in case their actual heads got damaged in the tomb), or if instead reserve heads were used during the funeral as part of religious ceremonies for protection.

Suggested reading:

Roehrig, Catharine H. "Reserve Heads: An Enigma of Old Kingdom Sculpture." In Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999, pp. 72-81.

Millet, N.B. "The Reserve Heads of The Old Kingdom." In Studies in Ancient Egypt, the Aegean, and the Sudan. Essays in honor of Dows Dunham on the occasion of his 90th birthday, June 1, 1980. Edited by William K. Simpson and Whitney M. Davis. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1981, pp. 129–131.

Ushabtis: Ushabtis (also commonly spelled "shabtis" or "shawabtys") are a type of small funerary figurine, typically made of faience, which became popular in the New Kingdom and later periods. They show a deceased individual in the form of the god Osiris: mummified, with arms crossed over the chest. The ancient Egyptians believed that they could be called on to do work in the afterlife (just as in life), but that these figurines could magically take their place and do the hard labor for them (in Egyptian, "ushabti" means "one who answers," i.e., responding to the summons to work). Ushabtis were often inscribed with the name of the person to whom they belonged and a spell that would "bring them to life," and sometimes came in large sets so the deceased could have one for every day of the year!

Sarcophagi: A sarcophagus (literally, "eater of the body" in Greek) is a coffin made of stone, usually limestone or granite. Sarcophagi could be inscribed with a deceased individual’s name and titles, and sometimes decorated. They could either be freestanding or carved directly into the rock of a burial chamber, and they often contained one or more nested wooden coffins which held the remains of the deceased.

Jewelry, scarabs, and amulets: Egyptians were sometimes buried with jewelry, including necklaces, rings, bracelets, anklets, and gold caps for the fingers and toes, as well as many other forms of personal accessories. A wide variety of different types of amulets (made of gold, copper, shell, ivory, faience, and/or various semi-precious stones) were found at Giza, sometimes strung onto jewelry and at other times as separate objects. Some of these types include: small figurines of gods and goddesses, animals, part of the human body, hieroglyphs, and sacred symbols. The Egyptians regarded amulets as important sources of protection because of magical properties they believed were associated with their shapes, the materials they were made from, or both. Two particular types of amulets were by far the most common throughout ancient Egyptian history. The scarab amulet took the shape of a beetle, which was thought to be a form of the sun god as he pushed the solar disk across the sky every day. The other most popular amulet was the "udjat-eye" (sometimes called "wedjat-eye"), which took the form of a falcon’s eye to refer to the god Horus, whose sacrifices for his father, Osiris, infused the eye with protective qualities.

Suggested reading:

Andrews, Carol. Ancient Egyptian Jewelry. London: British Museum Press, 1990.

Andrews, Carol. Amulets of Ancient Egypt. London: British Museum Press, 1994.

Stelae: A stela (also spelled stele, plural: stelae) is a slab, usually made of stone, which was inscribed with texts and/or images. Stelae could be either freestanding or embedded in a wall. They served a number of purposes: they could record royal decrees or proclamations; show an individual making offerings to the gods, as a sort of lasting prayer that could be left at temples; or be part of a person’s tomb, showing them receiving offerings to sustain them in the afterlife.

Archaeological Methods

While people have been visiting and exploring Giza for many centuries, the turn of the 20th century saw the development of scientific archaeology, which involves the meticulous documentation of everything the archaeologist finds while excavating. Archaeologists kept daily diaries, recording where on the plateau they were working and what they found; any objects they discovered were assigned a number, and described (and sometimes drawn) in a register book; photographs were taken and plans and drawings made to document the various stages of excavation. Today, Egyptologists are using increasingly sophisticated technological methods to record and study archaeological data in as much detail as possible. By recording the contexts of all discoveries, scholars are able to explore more complex questions about ancient Egyptian society and the lives, beliefs, and achievements of the people who built such a magnificent civilization thousands of years ago.

Suggested reading:

Manuelian, Peter Der. "Eight years at the Giza Archives Project: past experiences and future plans for the Giza digital archive." Egyptian and Egyptological Documents, Archives, Libraries 1 (2009), pp. 149-159.

Manuelian, Peter Der. "Excavating the Old Kingdom. The Giza Necropolis and Other Mastaba Fields." In Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999, pp. 138–153.

List of abbreviations of museums, institutions, and expeditions

- ÄMUL

- Ägyptisches Museum der Universität Leipzig (Germany)

- AWW

- Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien (Austria)

- BÄM

- Ägyptisches Museum, Berlin/Neues Museum (Germany)

- BBAW

- Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften (Germany)

- BM

- British Museum (England)

- BMA

- Brooklyn Museum of Art (USA)

- CBE

- Cairo University‐Brown University Expedition

- DUC

- Duckworth Laboratory, University of Cambridge (England)

- EMC

- Egyptian Museum, Cairo (Egypt)

- FMC

- Field Museum, Chicago (USA)

- GEM

- Grand Egyptian Museum (Egypt)

- GMBA

- Glencairn Museum, Bryn Athyn (USA)

- GPH

- Giza Project at Harvard University (USA)

- HM

- Hearst Museum, Berkeley (USA)

- HUMFA

- Harvard University-Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition (USA)

- JFKL

- John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum (USA)

- KHM

- Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (Austria)

- MFAB

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (USA)

- MLP

- Musée du Louvre, Paris (France)

- MMA

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (USA)

- MMS

- Medelhavsmuseet, Stockholm (Sweden)

- NCG

- Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen (Denmark)

- NHM

- Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna (Austria)

- OIC

- Oriental Institute, Chicago (USA)

- OSUT

- Osteologische Sammlung der Universität Tübingen (Germany)

- PMAE

- Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology, Harvard University (USA)

- PSNM

- Port Said National Museum (Egypt)

- ROM

- Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto (Canada)

- RPM

- Roemer- und Pelizaeus-Museum, Hildesheim (Germany)

- SHM

- State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg (Russia)

- SMÄK

- Staatliches Museum Ägyptischer Kunst, Munich (Germany)

- TUR

- Museo Egizio, Turin (Italy)

- UPM

- University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology (USA)

- VMFA

- Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond (USA)

- WAM

- Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts (USA)